Call it the anticolonial boomerang effect. In 1992, Antonio Benítez-Rojo describes the Caribbean as “an island that ‘repeats’ itself, unfolding and bifurcating until it reaches all the seas and lands of the earth, while at the same time it inspires multidisciplinary maps of unexpected designs,” likening the Caribbean orbit to the “spiral chaos of the Milky Way.” In his view, this ever-expansive reach — made perhaps with a counter-totalizing flourish to draw the ire of neocolonialists everywhere — is produced by the “technological-poetic” flow and improvisation of the Caribbean machine’s performative culture.

Akin to Amiri Baraka’s full-embodied reappropriation of the eurocentric typewriter in “Technology and Ethos,” Benítez-Rojo suffuses this archipelago’s people with a polyrhythmic dynamism to connect with the entire globe, and not solely via their feet: “to this end [they imbue] the muscles of [their] neck, back, abdomen, arms, in short all of [their] muscles, with their own rhythm, different from the rhythm of [their] footsteps, which no longer dominate.” Call it a wave of anticolonial boomerangs swinging to bomba, plena, reggaeton, soca, calypso, kompa, and more, y mas, et de plus, en meer, ak plis ankò…

However, Ian Baucom’s 1997 proclamation that we live in an “age of cartography” — with all of its attendant surveillance and free market-flow entrapments — signals a warning that bodies in movement are still tracked and trafficked even as they transform where they traverse. If Baucom suggests the metaphor of synapses as the articulatory “shipping routes” of this postcolonial re-worlding process, what conditionally controls their movement, and how do we measure the cause and effect of their anthralgia in the digital realm?

Curwen Best’s sobering 2008 measurement of the digital agency of postcolonial studies argues that because it has not “translated itself into an active actual movement with stated and practiced political, economic, and cultural activities,” online “versions of Caribbean society [have been] fashioned, constructed, and re-created” by publishing companies, universities, and journals who assert new forms of exclusive cultural ownership and circulation of Caribbean artists. As the island reflectively repeats, so does the plantation relationship.

In part, Best argues, this occurs because digital Caribbean cultural moves within “a medium that purports to purge itself of the burdens of history” (a sort of Thomas Friedman / Francis Fukuyama machine), and so “the ease of function and use of technology [mask] the underlying tensions that define cultural and practical relations.” To assert a conscientious movement to our movement, then, requires that we not just replicate Caribbeanness worldwide, but unmask how the horrors of cultural misrepresentation and economic theft now persist on sleek touchpad auction blocks.

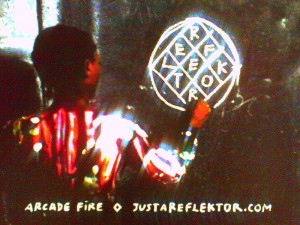

One provocative example of this critical intervention appears in an interactive video for the 2013 song “Reflektor” by the Quebecoise band Arcade Fire, created with webcam and phone technology from Google Chrome [experience the video before continuing to read, if you wish].

Set in Haiti, and featuring a woman’s techno-poetically surreal efforts to wriggle out of the viewer’s special effects control, the video packages a fantastical island scenario to be manipulated anywhere in the world that enjoys rapid bandwidth and requisite gadgetry. That is, until the woman chooses to take the power of cultural representation into her own hands.

Curwen Best warns, “[t]he exterior appearance conceals the gadgetry that dwells inside. The user therefore does not see or think of the mechanical or electronic processes that are at work and at play with the technology when using it. The exterior appearance therefore has the effect of making the world conjured up on the screen appear less forged and more natural in its simulation.” In our 21st century ever-present digital moment, “a reflection of a reflection of a reflection of a reflection” between humans and machines makes the synaptic work of representation a superficial trade that conceals how machinic value is historically based on earlier conceptions of human value, and in particular on enslaved African value. For this music video to document the Caribbean life that long created machines, and that continues to flow and thrive with unexpected designs on the other side of the shatterable screen, welcomes us to consider how to celebrate and also anticolonially shape the material world we inhabit.